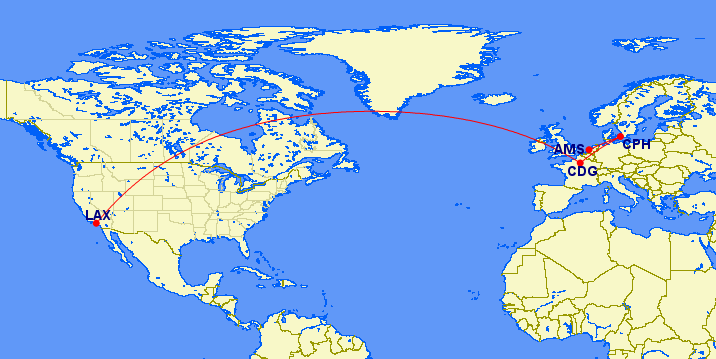

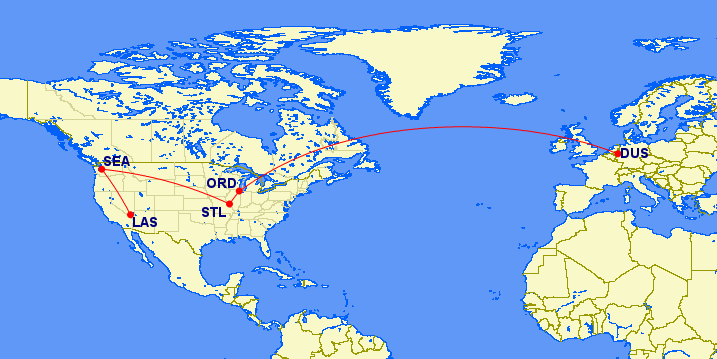

I just flew 13,588 miles from Los Angeles to Paris to Copenhagen to Amsterdam and back. The whole trip was flown in economy class and I only narrowly avoided Seat 31B. It truly was the worst seat in the plane on two separate legs of the journey, even though the aircraft types were different (Boeing 737 and Airbus A380). In fact, it’s so bad that KLM reserves the whole row 31 for crew use only. Instead, I was seated one row forward in Seat 30C for two legs of the journey. Somehow, I even scored an aisle seat.

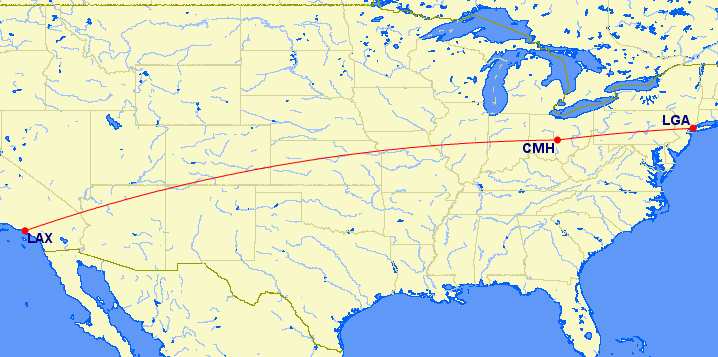

Exceptionally pleased with my good luck, I stored my carry-on luggage with an almost smug attitude on the final leg of my journey. It was a monster long leg, a nearly 12-hour flight from Paris to Los Angeles on the A380. Now, I was flying on an “attack fare,” and expected that something awful would likely happen. After all, apart from taxes, the seat was nearly free. I paid only $555 for a roundtrip flight from Los Angeles to Copenhagen on Air France, tacking on a cheap intra-Europe flight to Amsterdam with KLM so I could fly on a single itinerary (and avoid bag fees). It was the final leg of the journey, and I really couldn’t believe my good luck. A direct flight to the West Coast on an A380, and I didn’t even have to sit in the middle!

I took my seat, but a few minutes later I knew there would be a problem. A diminutive woman leaned over to me. “Would you like to sit by the window?” she said, a statement more than a question. “No, actually. I prefer the aisle, thanks,” I said. The woman started to crawl over me to her seat–clearly a novice flyer. “Please wait, I will get out, you can take your seat,” I said. “It’s OK, I can climb over,” she said, but I nimbly got out of the way and she was able to take her seat (she never really got the idea; it became a race the entire flight to get out of my seat before she tried to crawl over me). Just as I started to sit down, I felt a tap on my shoulder. It was her son. He was nearly 7 feet tall, a pile of gangly limbs with a tall pile of dreadlocks atop his head.

Now, the ceiling in the A380 is tall, but between this guy’s height and his crazy hair, the reading light was actually blocked! The other issue was the fact that he didn’t fit in his seat. At all. His diminutive mother sat in her window seat unmolested while this guy tried to wedge himself into his seat. Finally, he lifted the armrest. “Let’s leave this up for the flight,” he said, literally half of his body occupying my seat. “Let’s not,” I said. “It doesn’t work very well to do this when I lean back to sleep, and by the way, not to be annoying, but there isn’t actually room for me to sit in my seat.”

He adjusted himself, contorting his body into perhaps the most painful stress position I’ve ever seen–rivaling those the CIA perfected at Guantanamo–and managed to clear most of my seat. Unfortunately, his body still protruded into my seat, right elbow and knee and shoulder, everything hard and sharp periodically bumping into me as he tried to remain squeezed in his seat, limbs occasionally popping out of their stress positions to jam into me. Young people being independent, he didn’t want to try to share his mother’s seat, so everything moved gradually in my direction.

I lived for 3 years in Beijing. I am used to close quarters, and if you don’t learn to be tolerant of uncomfortable situations and inexplicable delays, you’ll just go crazy there. I learned to be more patient, and I’m still pretty patient–I haven’t been living in Western society long enough to lose patience, empathy and good humor. Still, this was an armrest battle on steroids. The battle in this case wasn’t over who had the armrest–trying to share it would have entirely been a lost cause–but whether the armrest stayed down and my seat-mate remained in only his seat. Every time I left my seat, I’d return to find the armrest up and half of my seat occupied. I mean, I didn’t blame the guy. I really sympathized. It isn’t his fault that airplane seats are designed to be a tight squeeze for Chinese people, let alone people who are nearly 7 feet tall. Still, leaving the armrest up just wasn’t going to work for me. I couldn’t exactly stand up for the whole flight.

In the end, I got almost no sleep. This was one of the longest and least comfortable flights I’ve ever taken. I honestly can’t even imagine what it was like for the guy next to me–a cruel, sadistic 12 hours of torture (gate to gate) no doubt. I think there really needs to be a better solution than this. The sizes of seats and people keep moving in opposite directions.

Do you have to fight for your whole airplane seat? Comment below!