As a frequent traveler and a member of the Global Entry program, I had gotten used to being able to get through borders and checkpoints quickly. When you’re a trusted traveler, long lines and intrusive questioning more or less go away. And this makes sense. In order to get a Global Entry pass, you have to give up a great deal of personal information to the government and pass an extensive background check. Just a lack of criminal history isn’t enough. While the Global Entry program selection criteria are secret, it’s widely believed that applicants are checked against a variety of law enforcement and terrorism databases. This information is combined with information about your known associates, employment, residence, travel patterns, and income in order to determine your level of risk.

Somehow, I was approved. I mean, there’s no reason why I shouldn’t be approved, but I do travel to some pretty unusual places. French Guyana (home of the European Space Agency’s launch site, one of the most incredible places I’ve ever visited). Suriname (reached by crossing a pirahna-infested river in a leaky dugout canoe). Even Palau. Combined with this, I’m pretty politically outspoken, and have even run for public office as an independent candidate. But none of this came up in the Global Entry interview. They just made sure my birth date was correct, verified my (lack of) criminal history, and took my fingerprints.

Fast forward a couple of years. The TSA implemented PreCheck, which–when combined with my Global Entry number–consistently got me expedited screening. I was able to get through airports quickly with a minimum of hassles until one day, I couldn’t anymore. I had been flagged, and was apparently added to a watch list. My days of easily crossing borders had come to an end. My crime? The government won’t say, but given the timing of the action, a dodgy-looking itinerary to Turkey is the likely culprit.

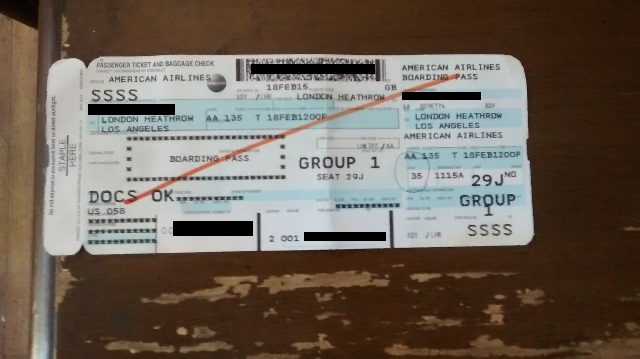

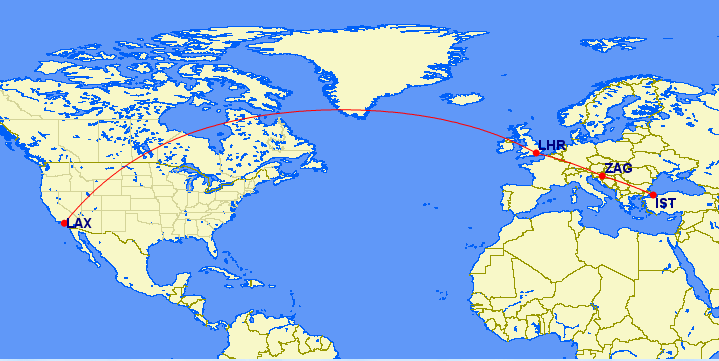

So, as red flags go, I think this itinerary would probably throw up about as many as possible. First of all, it was a one-way ticket. Second of all, it was actually two separate ticket numbers and multiple PNRs. I mean, this looks shady as hell. Why would someone take a flight that looks like an ordinary flight to London Heathrow, then book a flight a few hours later from London Gatwick to a secondary airport in Istanbul (which has connecting flights onward to all sorts of not-so-nice places in the Middle East), unless he was up to something?

Well, I was up to something. I was using frequent flier miles, and this is the sort of itinerary you end up with if you actually want to use your miles to go somewhere in Europe. You end up finding availability to secondary airports on inconvenient itineraries. My real destination was Zagreb, where my company has an office, but there wasn’t any availability to there. So I flew to the cheapest place from which I could get to Zagreb. I booked my onward itinerary to Zagreb as a round-trip ticket from Istanbul and threw away the return portion (because a round-trip ticket was cheaper than a one-way ticket). And then my return ticket from Zagreb was also booked on points–via London with an overnight, on an itinerary that I changed less than 2 weeks in advance due to an airline schedule change.

Istanbul-Zagreb, roundtrip ticket, throwaway return portion. Continuing on AAdvantage itinerary with overnight in London.

OK. Got all that? I’m really not surprised that the government didn’t either. Now, it wouldn’t have actually been hard for them to contact me to find out what’s up. After all, as part of my Global Entry enrollment, they have my home address, mailing address, employment address, email address, phone number, and fingerprints. Honestly, I’m not hard to find. And I have to wonder how many openly gay CEOs of online dating companies ought to be considered a more likely ISIS recruit than a likely target of an ISIS kidnapping and beheading! I was certainly paying close attention to my personal security in Istanbul, and didn’t take risks I normally would. Nevertheless, the Department of Homeland Security didn’t bother calling me to make sure I was safe in Istanbul, or offer me any assistance (as the Japanese embassy did to all Japanese citizens in the Middle East after Japanese journalist Kenji Goto was kidnapped). Instead, I was flagged as an imminent security risk to commercial aviation and apparently (although they won’t confirm or deny this) ended up on a watch list.

The TSA has two lists, neither of which are good to be on. The first and most carefully vetted list, with the smallest number of people, is the “no fly list.” Being on this list means you’re not allowed on board any flight to, from or through the United States (including flights that pass through US airspace). And if you’re on this list, you probably belong on it. According to documents leaked to the press and the ACLU in 2013, the criteria for being on this list are criteria I can fully get behind. The government needs to not only be pretty sure that you’re a suspected terrorist, but also that you’re what they consider “operationally capable” of committing a violent act of terrorism. So, it’s not enough just to be a suspected terrorist. You have to be in the actual process of doing bad terrorist stuff, having taken tangible steps toward committing an act of violent terrorism. And for this purpose, “terrorism” isn’t the all-expansive, politically motivated definition of essentially any opposition to the Obama Administration and its wrong-headed policies, but the real deal: actual violent stuff, really and truly bad guys. There are a couple of other categories of people who end up on the no-fly list, including former Guantanamo Bay detainees and known insurgents fighting US troops abroad. Basically, the No Fly List is full of really bad people. Nevertheless, if you’re a US citizen and you end up on the no fly list, the TSA can still issue a waiver on a case-by-case basis and allow you to fly (this seems to be intended to allow US citizens placed on the list to return home from abroad). In short, people on the No Fly List aren’t people I would want to be on the same plane with, and it’s not easy to end up on this list.

And then there is the list I apparently ended up on. This list is called the “selectee list.” These are people (like me) who are still allowed to fly, but are subject to additional security screening. You can also run into trouble at the border, and extra questioning and searches. Or, as is more often the case, you’re someone who is misidentified with a person on the list. You can end up on this list for a very large number of reasons, and the ACLU has sued the government repeatedly in an effort to reduce the number of innocent people ensnared and provide citizens with more effective redress procedures. One of the ways that you can reportedly end up on this list (there are an expansively large number of ways this can happen) is by making travel movements to known terrorist hotbeds for which no legitimate explanation for the travel exists. On the surface, this probably makes sense. And objectively, my travel to Turkey probably looked pretty shady absent any context. However, it’s an open question what efforts the government makes to obtain any actual explanations for suspicious activity. In my case, one phone call to me–or even an email to the UK Border Force, who asked me about my unusual itinerary in detail at Heathrow–would likely have cleared everything up.

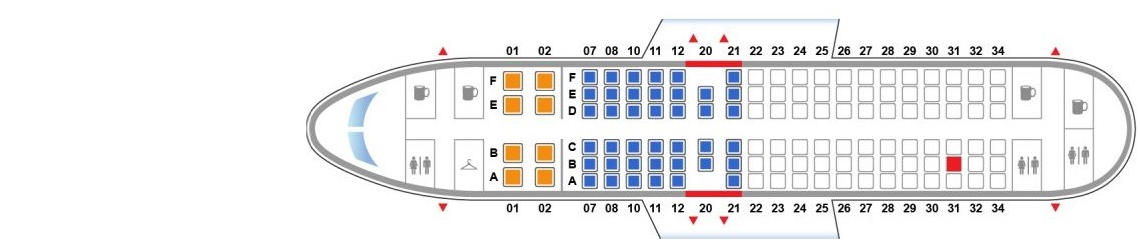

What happens when you are on the selectee list? Even if you have Global Entry, you can no longer check in online. You have to check in at the airport counter, which really sucks if you’re flying an airline (such as Southwest) that doesn’t allow reserving seats in advance. I am usually stuck in Seat 31B anyway, but I’m virtually guaranteed this now. Your boarding passes are flagged with SSSS, and you need to obtain a stamp from the TSA after you are screened and prior to being allowed to board (TSA agents will also often meet you at the gate and retrieve your boarding pass). The TSA doesn’t always remember this, so you might miss your flight if you discover that your boarding pass hasn’t been stamped. Your bags are also tagged with SSSS and receive extra scrutiny, so if you check bags, be sure to allow extra time in advance. Otherwise they might not make the flight you’re on.

When you present yourself at the security checkpoint, you are assigned a TSA escort who stays with you until the checkpoint. This can actually be a good thing–if the TSA is short-staffed (like they usually are at LAX) and can’t waste a half-hour waiting in line with you, they’ll just cut the line with you and escort you to the front. You will receive the same type of screening as if you refuse to walk through the body scanner or have forgotten your ID. This means aggressively being frisked all over your body, having your genitals and (if female) breasts groped, and having to undo your pants so the security officer can feel all the way around. All of your electronics have to be powered on, so be sure you have a full charge on everything. Everything you have will be scanned for explosive residue, so hopefully you aren’t an Army ranger, the owner of a fireworks stand, or a pyrotechnician. All of your bags will be gone through manually in addition to being X-rayed. While the TSA might look the other way on liquids or gels for most people, every rule will apply to you to the letter. The whole process takes an extra 10 minutes or so at the checkpoint versus a normal screening, unless the TSA finds anything not to their liking and decides to question you further. This could take even longer. And although you’re allowed to proceed on your own to the gate, you’re often required to board last. So, in addition to being stuck in a middle seat, you’re virtually guaranteed no space in the overhead bin. TSA agents will double-check your boarding pass for their magic stamp before you’re allowed on board. All told, it takes the fully dedicated resources of about 10 people to get you on a plane each time you fly–your tax dollars at work. Thanks, Obama!

There is a redress procedure, which I filed. I provided a detailed explanation about myself and my travel that explains everything that might look unusual without understanding the context. Today, I received a letter which said, in effect, that the TSA will neither confirm nor deny whether I was (or am) on a list, but it provides a redress number I can use the next time I fly to ensure that I am correctly identified. So, we’ll see what happens on my next flight. Hopefully, sanity will prevail. In the meantime, if you end up on a watch list, you can at least know what to expect and plan accordingly. And given this experience, I am only strengthened in my resolve to follow the lead of Tim Cook and Apple at Cuddli when it comes to digital privacy issues.